Clothing does not merely cover the body. It covers stories. It covers secrets. It covers scars that run through culture, memory, and lived experience. We like to believe that a garment is a neutral shell, a simple textile arranged around a human frame, but the truth is far more complicated. Every pleat, every uniform, every pinstripe suit is a kind of coded vessel, carrying within it an emotional cargo of desire, repression, rebellion, pride, trauma, and dreams that have been stitched into its seams by history itself.

Fashion often obsesses over novelty, reinventing silhouettes, chasing shock, discarding yesterday’s ideas in the hope of tomorrow’s applause. But true design fluency goes beyond invention. It is about excavation. It is about seeing garments as living repositories of contradictory feelings and social truths. It is about unearthing the subtle, often repressed emotional forces hidden inside culturally coded garments, then freeing them, transforming them, dignifying them through new form, color, material, and posture.

The greatest designers have understood this. They did not become revered by simply redesigning the world from scratch. Instead, they reached into the history of familiar garments, the trench coat, the tailored suit, the school uniform, and extracted a feeling or truth long dormant within them. They reimagined these truths to resonate with the needs and desires of their time, making what was hidden visible, what was silent speak, what was numb come alive again.

This is the deeper mission of the designer: not merely to decorate, but to reveal. Not simply to provoke, but to understand and to elevate. In decoding the hidden language of a garment, the soft pleats of submission, the starched folds of discipline, the armored lines of masculine suiting, the designer has the power to make these buried truths visible, to give them voice and beauty, so that the people who wear them can feel not just dressed, but seen.

Cultural Codes, A Brief Primer

Every culture is a web of codes, rules and meanings that shape what we wear and how we wear it. These codes are so deeply embedded that we rarely stop to question them. In fashion, they surface through silhouettes, fabrics, colors, and construction techniques that carry messages beyond their practical use. A uniform does not just clothe a body; it signals hierarchy, belonging, discipline. A suit is not simply a tailored shape; it projects control, authority, and the rational order of business. A pleated skirt looks sweet and obedient at first glance, but is rooted in histories of surveillance, purity, and the policing of feminine bodies.

These garments are like cultural fossils, preserved forms that contain the emotional DNA of entire eras. They operate almost like a Trojan horse, carrying centuries of hidden beliefs and psychological patterns inside their folds. They remind us of how people were trained to perform their roles in society:

The military trench coat: heroic masculinity on the surface, but beneath, a longing for softness, for peace, for relief from brutality.

The maid’s apron: invisibility and labor, but also quiet pride, domestic skill, and unspoken dignity.

The clerical robe: spiritual authority, moral purity, but also the weight of dogma, secrecy, and power unchecked.

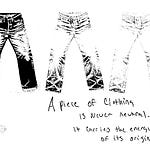

The denim workwear jacket: the uniform of the laboring class, resilience stitched into its seams, but also the history of exploitation and survival.

We connect to these garments often without realizing it. Why? Because they tap into collective memory. Like a song you didn’t know you remembered, they spark something deep and instant, a recognition that bypasses logic and speaks directly to emotion. These garments are charged with meanings we inherited, from stories we heard, movies we watched, rituals we witnessed, roles we were expected to play. They become a kind of emotional shorthand, a language we all somehow know how to read.

The greatest designers have known this, and have used these codes masterfully:

Miuccia Prada: reimagining schoolgirl uniforms and modest shapes to expose the tension between submission and rebellion.

Rick Owens: taking the cloak and the tunic, garments of ancient ritual, and turning them into symbols of modern, dystopian spirituality.

Martin Margiela: deconstructing the tailored suit to reveal the fragility and impermanence behind structures of power.

Wales Bonner: reframing military and colonial silhouettes to speak to Black identity, resilience, and poetic resistance.

Rei Kawakubo (Comme des Garçons): distorting the corset and crinoline to confront ideas of beauty, restriction, and the grotesque.

This is why culturally coded garments are so effective for designers. They allow you to connect to an audience instantly, because the form is already familiar, it carries meaning before you even touch it. But by altering it, through silhouette, fabric, color, or construction, you can awaken new truths, speak to new fears and desires, and create something that feels both known and shockingly fresh.

These codes are not creative limitations; they are creative goldmines. They are raw material for emotional storytelling, preloaded with meanings that can be challenged, reimagined, and reborn. They invite the designer to ask: What truths lie dormant in this garment? Whose hidden stories am I ready to set free?

The Emotional Cargo Within Garments

Beneath the surface of every culturally coded garment lives a hidden cargo of emotion, a freight of contradictions, longings, and psychic tensions that go far beyond mere function. These garments are not passive objects; they are living archives of how human beings have navigated society, gender, class, power, and vulnerability across time.

Consider the pleated skirt. At first glance, it seems harmless, even charming, a symbol of girlish order and conformity. But look deeper, and it reveals a choreography of restraint, a garment meant to regulate the female body, to present a legible, “pure” femininity while masking emerging desire, sexual awakening, or rebellion. The pleats, stiff and repetitive, become bars of a cage disguised as beauty.

Or the sharply tailored suit. Its architecture is a monument to power, rational, symmetrical, severe. It seems to grant its wearer authority and protection, but inside that armor, there is often an equally powerful story of suppression. The suit erases softness, asks its wearer to perform a version of self built around hierarchy and competition, and silences more tender or ambiguous truths.

A corset is another perfect example. It is at once a sculpture of feminine ideal and a torture device, contorting the body to meet impossible ideals of virtue and beauty. And yet it also carries a secret eroticism, the intimate contradiction of being both restrained and provocative, concealed and exposed.

These emotional tensions are the true power of coded garments. They are layered, contradictory, and deeply human, and they resonate because they mirror the complexities of the people who wear them. Our garments become an externalized stage for our own internal conflicts. We long to be seen, but we fear exposure. We desire freedom, but we are conditioned to obey. We want to belong, yet we crave individuality.

The designer’s task is to listen for these contradictions and bring them to the surface, to free these truths from their historical silences and give them new voice, new posture, new color, new material. When a designer exposes the hidden emotional cargo of a garment and reinterprets it, they create a profound recognition: the audience sees themselves in it, not just through nostalgia, but through an amplified, dignified retelling of their own emotional reality.

This is why working with historically coded garments is so potent. It is not about fetishizing the past, but about pulling forward its dormant truths, the loves, the losses, the unspoken desires, and re-enchanting them for the present. In doing so, the designer helps us to wear our hidden stories on the outside, to transform private contradictions into public, visible, and even beautiful statements.

The Designer as Translator and Liberator

A true designer is not merely a stylist chasing novelty. A true designer is a translator, fluent in the hidden language of garments, and a liberator of the truths sewn into their seams. They enter the archive of clothing’s long memory and listen for what has been silenced, but also for what has been cherished. They decode both the wounds and the wonders woven into cloth.

Think of garments as living artifacts, each holding centuries of layered instruction: be disciplined, be graceful, be proud, be protected. Within these folds live not only commands of power and obedience, but also gestures of beauty, solidarity, tenderness, even transcendence. These codes are rarely black and white; they are saturated with contradictions, noble and cruel, liberating and restricting, all at once.

The designer’s role is to approach these contradictions with curiosity rather than judgment, to explore their depths, to feel their emotional temperature, and to translate them for a new time. Through silhouette, color, fabric, and movement, the designer can reveal a fuller spectrum of truth, not only the repressed suffering but also the hidden dreams, dignities, and moments of quiet pride that garments carry.

Consider a suit: a monument to structure and patriarchal hierarchy, yes, but also a symbol of self-possession, confidence, and ritual pride. Or a pleated school skirt: an emblem of discipline and innocence, yet layered with nostalgia, freedom of youth, and the thrill of first rebellion. Even the military trench, beyond duty and heroism, holds stories of camaraderie, resilience, and survival in its weather-beaten cloth.

The designer is the one who reaches into these layered archives, pulling out the truths that resonate with the current audience, amplifying what feels needed, what feels true, what feels beautiful now. It is a form of emotional editing, choosing which parts of the garment’s myth deserve to rise to the surface and which may finally be left to rest.

In doing so, the designer creates more than a garment: they create a mirror. A mirror that reflects the complexity of our inner lives, our contradictions, our memories, our quiet forms of courage, and makes them wearable, seen, dignified. This is not mere decoration. It is an act of cultural and emotional translation. It reminds people that they can carry their layered truths with pride, that no feeling is too complex to be honored, and that beauty can emerge precisely from that complexity.

At its highest level, this practice is a quiet revolution. It frees clothing from hollow trend cycles, and frees people from hollow identities. In that moment, the designer becomes not just a maker of garments, but a liberator of the human spirit, one who gives shape to our tangled, layered, unspoken realities, and makes them worthy of admiration.

Beyond the Archetype: The Designer as Mirror of Human Complexity

People do not want to be shoved into a box. They do not want to be reduced to a flat archetype or an easy costume. So much of the fashion industry is obsessed with packaging people into simple, predictable characters: the rebel, the seductress, the executive, the ingenue. These lookbooks and style guides might sell a quick story, but they rarely honor the tangled, contradictory, and deeply personal realities of the people who actually wear them.

The truth is, human beings are far more complicated than any neat label. So much of what we do, whether we admit it or not, is driven by the desperate hope of being seen, heard, understood. Most people go through life starving for recognition, longing to have the nuanced, unspoken parts of themselves registered by the world. That hunger is universal. It is one of the deepest human desires.

Clothing, all too often, becomes a tool of oversimplification, a shortcut that reduces a person’s rich, layered identity to a hollow silhouette. Uniforms of trend conformity. Templates for social belonging. But these often flatten the very things that make us alive: our contradictions, our dreams, our wounds, our personal mythologies.

A great designer refuses to flatten people. A great designer knows that the most powerful gift you can give someone is to reflect them accurately, to capture not just their social category, but their private emotional weather, their hidden truths, their subtle shades of becoming. If you can do that, if you can transmute their unspoken realities into form, function, color, and texture, you will not just sell clothes, you will create devotees. People will line up for your work because you gave them something they have been craving: to be seen. To be recognized. To be made beautiful, in all their complexity.

It is a feeling like finally finding the right words to articulate a difficult, buried truth. That rush of clarity, someone finally understood me, someone finally captured exactly what I meant, is profoundly liberating. Clothing can deliver the same catharsis, but through silhouette, shape, color, and material. When a designer gives someone the chance to wear their interior truth, they are offering them a form of radical self-recognition. That is unforgettable.

What does this have to do with historically coded garments? Everything. Because these garments are the archives of countless people’s hopes, fears, and roles, complex, layered, often contradictory. To truly wield these garments is to study them with empathy, to decode their emotional payload, and then to reshape them with nuance, respecting their histories while rewriting them for new realities. That takes a savage kind of brilliance, the ability to read between the cultural lines and write a new visual language that honors the hidden truths of human experience.

A designer who can do this, who can excavate and animate these layers with precision and care, does not just design clothing. They write new cultural mythologies. They become a mirror to the human soul, reflecting back a truer, more dignified portrait of who we really are. And people will never forget the one who made them feel seen.

Historical Garments as Mythic Frameworks

There is something profoundly timeless about historically coded garments. Beyond their visible form, they carry a resonance that is almost mythological, an echo of universal human truths that we all, to some degree, recognize and desire. These garments act like archetypes, they encode the fundamental desires and tensions that define what it means to be human.

Consider the suit. Its structure, its symmetry, its weight, it is more than a uniform of corporate power. It is a kind of temple of order, a sacred architecture that speaks to our collective longing for stability, authority, and the security of belonging to a hierarchy. Even if we reject its strict associations, part of us is drawn to the promise of control and self-possession it offers.

Or think of the military trench coat. It is a silhouette of duty and resilience, but also a narrative of courage, survival, and collective sacrifice, myths as old as any epic poem. Even when reimagined in modern colors and fabrics, its lines retain a heroic undercurrent that resonates deeply with people.

These garments are not static relics. They are frameworks, narrative vessels that move through time like mythological stories, retold, reshaped, reimagined for each new era. They function in fashion exactly the way ancient myth functions in literature or film: they offer a durable structure, a familiar emotional grammar that designers can use to build something new and culturally specific.

It is much like the hero’s journey in storytelling, a narrative template that has guided myths for centuries and still appears in modern blockbusters like Star Wars. Audiences connect to these deep, recurring structures because they mirror something elemental about the human experience. Historical garments serve a similar role in visual storytelling. They hold a shape, a symbolism, a drama that feels innately human.

But people do not want to be reduced to these archetypes alone. They want their personal complexities layered over them. They want the suit that also shows their vulnerability, the trench coat that carries softness, the uniform that contains a hidden rebellion. In this way, historically coded garments are starting points, a skeleton of meaning on which designers can build a new flesh of nuance, emotion, and modern relevance.

To wield these garments skillfully is to stand inside a river of human continuity. You are using forms that have been charged with the hopes, fears, triumphs, and heartbreaks of generations before you, and then you are rewriting them, bending their narrative to express the current moment. You are performing a kind of cultural myth-making, giving people a chance to wear not only who they are today, but who they have always been and who they might yet become.

This is why historically coded garments are so powerful. They carry a weight of human storytelling that is almost impossible to replicate from scratch. They let designers tap into a timeless, nearly unconscious recognition, and then transform it, elevate it, and reframe it for a new age. In doing so, designers do not just create clothes. They write a new mythology for a generation hungry to see itself reflected in a more complex, honest, and dignified way.

Why Historical Garments Hold Us

There is a reason historical garments refuse to vanish. They persist across centuries not by accident, but because they speak to something rooted deep in the human condition. We are creatures of tension: we crave individuality, the chance to express our singular selves, but at the same time we ache to belong, to feel tethered to a collective greater than us.

Historical garments hold these contradictory longings in perfect balance. They are living emblems of a shared reality, a subtle proof that while our stories are personal, they are also deeply communal. When we slip into a garment with centuries of cultural meaning, we are stepping into a lineage, a chain of humanity that reaches backward and forward in time. These clothes are a kind of social glue, binding us through memory, myth, and a shared emotional DNA.

Humans are wired to connect. No matter how loudly we declare our independence, we are social beings who yearn to be seen and to be part of something larger. Historical garments allow us to inhabit both impulses at once. They give us a framework of belonging while still offering space for the personal truths we carry. They are a bridge, one foot planted in collective history, the other in our private emotional landscape.

That is why these garments survive, generation after generation. They are not merely cloth, they are containers for qualities we admire, for virtues we still find useful, for archetypes that still resonate. They mirror the best and worst of what humans have been, and they remind us that no matter how different we think we are, there is a web of shared humanity that connects us across time.

Wearing these garments, reinterpreted with nuance, feels like joining a conversation centuries in the making. It feels like belonging. And in a world where alienation and hyper-individualism threaten to isolate us, that sense of belonging, even through a pleat, a lapel, a stitched buttonhole, is nothing short of profound. a

The Designer as Myth-Maker of Our Time

In the end, the role of the designer reaches far beyond cut, cloth, and commerce. It is closer to the role of the myth-maker: someone who takes the raw material of collective memory and individual longing, and gives it form, meaning, and beauty. Historically coded garments are among the richest raw materials available, they carry the emotional architecture of centuries, the deep grammar of what it means to be human. They hold our contradictions, our fears, our pride, our desire for belonging, our unquenchable need to be seen.

But these garments are not fossils. They are living codes, waiting to be reactivated and reimagined. They can be bent toward the truths of the present, layered with the subtle emotional realities of modern life, and retold as new mythologies for a new generation. This is the quiet superpower of the designer: to see these codes not as cages, but as canvases, to sense the complexity within them, to rescue what is worth preserving, to transform what must be challenged, and to make the entire tangled, layered truth beautiful.

When you do this, when you design in a way that allows people to feel fully recognized, accurately reflected, and dignified in their contradictions, you do more than dress them. You give them permission to be fully human. You give them a language to articulate what words cannot. You become the custodian of their personal myth, their hidden longings, their half-buried dreams.

And in return, people will follow you. Because you did what no trend or hollow archetype ever could: you saw them. You showed them that their complexities could be worn, that their truths could be made beautiful, and that their humanity deserved to be visible.

In a world obsessed with the superficial, that is nothing short of revolutionary.