The Comprehension Trap and the Death of Newness

You ever wonder why everything, even the “new,” feels like something you’ve seen before? Why every collection, every drop, every campaign feels just familiar enough to be digestible, but rarely strange enough to be exciting? That’s not a coincidence. That’s the system working exactly as it was designed.

We live inside what I call The Comprehension Trap, a cultural economy where value is determined not by depth, not by originality, but by how instantly something can be understood. Attention is the currency, and comprehension is the toll to even earn it. In this system, fashion isn’t judged on vision, it’s judged on how fast it can be processed, screenshot, and shared. And that’s a death sentence for real innovation.

Designers are no longer incentivized to create something genuinely new. They’re incentivized to create something that feels new, but actually confirms what we already know. We mistake familiarity for brilliance, and instant recognition for value. We say we want surprise, but only if we can explain it in five seconds. We crave discovery, but without discomfort. This contradiction is choking the oxygen supply to creativity.

So what do we get? A fashion system optimized not for exploration, but for Recognition Addiction, the cultural impulse to reward only what we already understand. If a collection doesn’t “click” immediately, we scroll past it. It doesn’t go viral. It doesn’t sell. Designers know this. So they pre-digest their work. They insert logo bait, nostalgia pieces, algorithm-friendly silhouettes. Not because they should, but because they must to stay visible. They fear silence more than failure. They fear being misunderstood more than being forgettable.

And the result is everywhere. A dulling sameness. A creeping aesthetic compliance. Collections that are technically polished, perfectly styled, instantly legible, and emotionally hollow.

But it wasn’t always like this.

When Rei Kawakubo debuted Lumps and Bumps in 1997, people didn’t just misunderstand it, they mocked it. Critics laughed. Some walked out. Many had no idea what they were seeing. And yet, decades later, we still reference that show as a seismic moment in fashion history. Why? Because Kawakubo didn’t chase comprehension, she dared the audience to sit with discomfort. She gave us something that refused to explain itself. And in time, it redefined beauty.

Now imagine if she had been told that her collection had to “make sense” in five seconds. That it had to go viral. That it had to include a recognizable bag, or a jacket cut from the archive, just to keep the masses calm. Imagine how many radical visions would have died under the pressure of The Comprehension Trap.

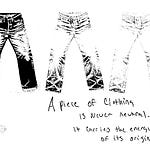

We no longer allow things to breathe. To linger. To confuse us. Everything must arrive fully formed, explain itself instantly, and flatter our existing tastes. And in doing so, we’ve amputated one of the most vital functions of fashion, its ability to reveal something we didn’t know we needed. Not what we already like, but what we could grow to love, slowly, awkwardly, unexpectedly. Fashion, at its best, doesn’t just mirror who we are, it shifts us. It introduces tension, unfamiliarity, even discomfort, and in that space, something transformative happens. But that requires patience. It requires space to misinterpret, to return, to re-see. When we strip that away in favor of immediate clarity, we lose the long arc of emotional resonance. We lose the garments that haunt us months later. We lose the collections that age in reverse, strange at first, unforgettable in hindsight. We don’t need more things to “get.” We need more things that get to us, slowly, deeply, and without permission.

We keep asking why fashion feels stagnant. Why nothing cuts through. Why it all blurs into an endless remix. But we rarely question the perceptual system we’ve built, one that punishes slowness, ambiguity, and risk. One that rewards only what feels instantly familiar. That is Recognition Addiction, and it is the lifeblood of The Comprehension Trap.

If fashion is going to feel alive again, we need to break that addiction. We have to stop demanding that collections explain themselves on arrival. We have to retrain ourselves to sit with what we don’t yet understand. Because the shows that haunt us, the pieces that move us, the designers who change the culture, they’re never the ones we “got” right away. They’re the ones that made us work for it. And in a culture built on immediacy, that kind of resistance might be the most radical thing a designer can offer.